Hope River: Poet Partnership to Cope with Climate Change

Last November, I was approached with a fantastic opportunity to inspire hope in Davis’s youth. Julia Levine, the poet laureate of the city of Davis, had noticed in her years as a child and family psychologist that an increasing number of young adults were struggling with the realities of climate change and failing to see a bright future for themselves. She conveyed to me, as well as other volunteers, that adolescents generally don’t have the coping mechanisms to deal with big issues like climate change and have been exposed to so much negative information surrounding the topic that they often felt as if they were alone in their concern and helpless in their ability to do much about it.

Julia wanted to change that. She enlisted the help of other poets as well as experts in projects that are aimed to reduce the impact of climate change, like myself, to create Hope River. This project taught middle school aged children at DaVinci Charter about expressing themselves through poetry, as well as exposing them to projects like electric vehicle charging, tree planting, and composting to show kids that people are working on these problems. The students would then write poems about what they learned and read one of them into an app which would then allow anyone walking the bike path to the school to hear the poems read by the student-authors.

When told about this opportunity, I was immediately on board. When I was in middle school, and even a little before, I remembered hearing about “global warming” and learning that there may no longer be ice in the arctic nor polar bears within my lifetime. I threw myself into art, drawing pictures of animals and making bags with fabric markers that said, “Save the Polar Bears.” Because of these childhood fears, I subsequently pursued a degree which allowed me to work in environmental restoration prior to my entry into the UC Davis Environmental Policy and Management program. I knew what these students were going through, but in the nearly 15 years since I was in 7th grade, climate change has become much more apparent.

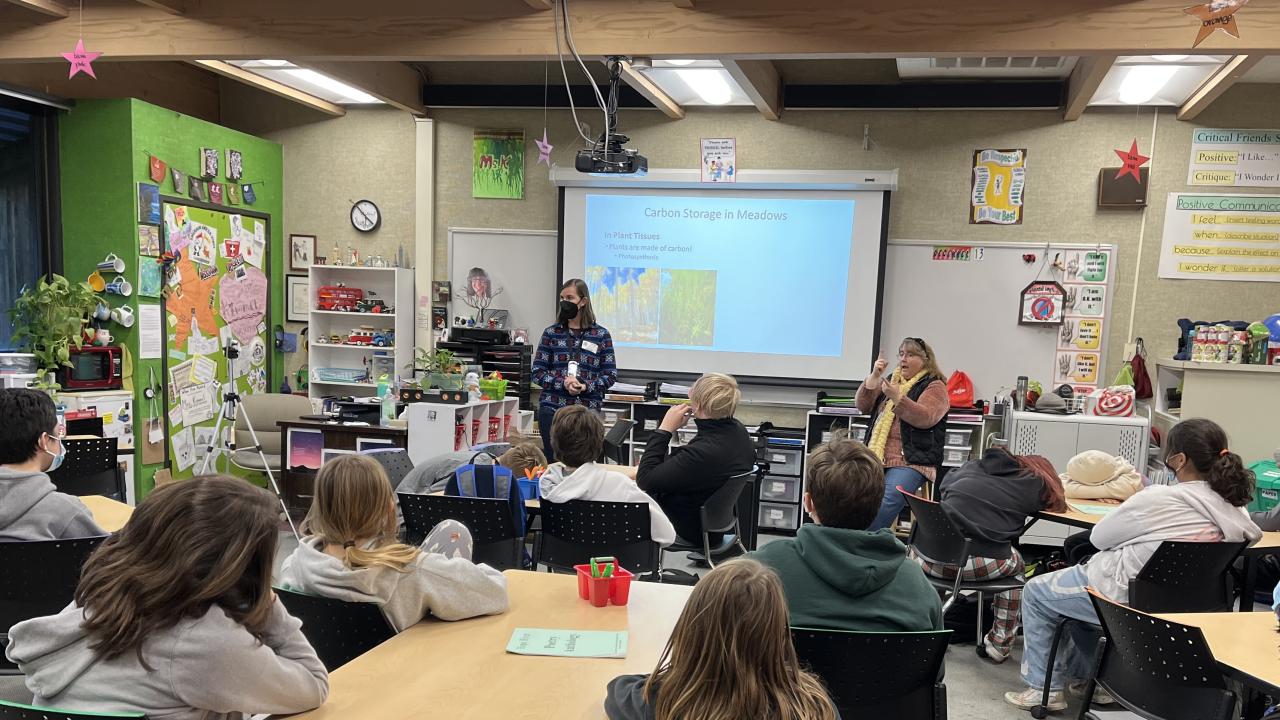

I presented in a 7th grade class in mid-December about my previous work restoring and monitoring montane meadows. Wet montane meadows are high elevation meadows that stay wet for a majority of the year. They are largely covered by rushes, sedges, and wildflowers that can withstand the saturated soils. I had been involved in a large project measuring greenhouse gas releases and sequestration of disturbed, undisturbed, and restored wet montane meadows in the Sierra Nevada shortly after graduating in 2018.

The results of this study were extremely heartening: 1. Wet meadows in good condition store much more carbon than the surrounding forest, rivalling nearly that of a tropical rainforest and 2. Restored wet meadows, if they haven’t hit a tipping point, are no different in their carbon sequestration ability than those that have never been disturbed. Another piece of good news I shared with the students is that restoring wet montane meadows is often a relatively easy and affordable process, involving beaver dam analogues, lengths of willow branches to form a “dam” across incised channels, which allow sediment to collect and slows water into braided channels. Ideally, beavers would then move in and keep the system in good health. This both allowed for large amounts of carbon storage by reducing decomposition rates as well as water storage to prevent floods further down the watershed.

The students were very engaged and asked great questions. One 7th grader asked if there were any downsides to having beaver dam analogues instead of beavers, and we were able to discuss some of the pros and cons, like having to perform some maintenance ourselves if beavers aren’t in the system or the risk of beavers damming too close to homes. Students were also able to connect why wet meadows stored carbon well to a class project they had done where they added too much water to a terrarium on accident and it had killed off the worms. We were able to discuss that if some decomposers, like worms, couldn’t survive in the system because it was too wet, then the carbon would be buried underground instead of being released into the atmosphere.

When it came to the poetry section, students were open to sharing their topics. Some were light hearted. One student wrote about how beavers are important influencers to the system, so made a joke about a beaver being a social media influencer. However, some showed a lot of depth and concern. Another student wrote about being the sun, watching the Earth slowly warm as humans caused its demise, and all the sun could do was watch.

As adults, we may not like to think that children understand and fear large scale problems like climate change, but we need to face the reality that they do. If we downplay their fears, we risk making them feel isolated and powerless. However, we also cannot expect children to figure out on their own that the adults of the world are worried too and so are doing our best to find solutions. Hope River does not shield children from the huge problems that climate change poses. It gives children faith that despite what they may hear on the news, there are still people out there that haven’t given up hope, so neither should they.

Asia Jones is a second-year student in the EPM program. Prior to beginning her masters, she was an Americorps member in the Sierra Nevada Americorps Partnership (SNAP), working with the South Yuba River Citizens League (SYRCL). During this time, her primary role was collecting greenhouse gas data in wet montane meadows in the Sierra. This work, as well as the work of many others, culminated in a recent publication in the journal Ecosystems.